07 Feb Indian Rope Trick

Part I

Sometimes when I opened the front door of our house in the port city of Kingston Upon Hull on the north east coast of England I would find that a grey wall had been built immediately in front of it.

It appeared to be solid, but it was not.

It was fog from the North Sea.

That it was permeable was suggested by a glowing street lamp floating somewhere in the distance like a wandering autumn sun, but that insubstantiality served only to make the wall more sinister, because I knew that although I could step through it, once I had done so I would disappear.

Quite literally. Not only I myself would vanish from the sight of any humans in the house – but the house itself would vanish from my sight with as much finality as the coast of Spain had fallen away behind Columbus when he set out across the Atlantic with the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.

Nevertheless, I could no more resist the call of the unknown than could the great navigator himself – and out into the fog I would step, pocket money clutched in my hand, head held high. And would proceed to feel my way along the damp privet hedges of Summergangs Road like a blind person.

Fog was frequent in Hull because ever since the last ice-age the entire east coast of England has been steadily tilting itself into the North Sea and whenever the weather is right the fog sidles over the cold, pebbly beaches, up the muddy rivers once used by Viking visitors with names like Ivar the Boneless and Thorfinn Skull-splitter – and on through backyards stiff with frozen washing into the streets of the city itself.

I was never lost, though. I always found the bus stop at the end of the street, and waited there until the lights of the top deck of the bus appeared in the mist, like a Spanish galleon, some lost straggler from the Armada, emerging out of the past to carry me away.

The bus stop, by the way, was simply a sign attached to a tall dark green wrought iron lamppost, and it served as the stop for the school bus. In Hull parents did not accompany their children to school even on their first day: they simply sent them to catch the bus.

This system was generally successful, though a boy named Paul Kaley was so terrified of the prospect of his first day at school that as the bus bore down on us he swarmed up the lamppost and clung to the crossbars like a monkey on a stick.

I remember how the driver stopped the bus, climbed up the lamppost after him, and dragged him bodily down before hurling hurled him into the interior and driving off.

I think there are few transport operatives who would offer their customers that kind of service nowadays.

But this particular day isn’t a school day: it’s a Saturday morning and I’m headed for town, with sixpence in my pocket and a world of infinite possibility stretched before me.

Once aboard number 24A and heading west down Holderness Road towards the city centre I could look down from the top deck, right over the driver on the floor below so that one could imagine one was in control of the entire glorious enterprise – and watching the familiar shops of East Hull disappear behind me into oblivion.

As the bus approached the river down Holderness Road the side streets crowded in, Jesamond Street, Dansom Lane, Mersey Street, each smaller and meaner than the last, each deeper in the almost tangible smells rising from the seed-oil mills, breweries and tanneries along the River Hull. My mother had grown up in those streets, but had escaped.

And then the bus reached North Bridge from which you could look down on the River Hull itself – a narrow waterway the colour of a Starbucks latte, flowing between banks of even browner mud as it made its way towards the sea.

The river seemed narrower than it was because of the mills and warehouses on either side of it, towering high and shutting out the light. The water was spanned by a massive iron bridge, studded with more bolts and rivets than Captain Nemo’s Nautilus, and could be raised and lowered at will.

This bridge featured in my dreams for many years as an object of terror, as a result of an incident that took place when I was perhaps three years old.

My mother had joined a church in West Hull, to which she took me from our home in East Hull on the back of her pedal bike, on which my father had built me a little seat.

One day, as we were on our way to this church, my mother was obliged to stop her bike at the river’s edge while North Bridge was raised for a passing ship. I can still see its massive metallic bulk as it rose over our heads, momentarily blotting out the sun, and the great depth of the drop down to the river.

I can still bring back the sensation as I fell.

The reality is that I fell from the seat on the back of the bike onto the road: a distance of possibly thirty-six inches, which left me, not surprisingly, entirely uninjured.

But when the event was replayed in my dreams, I fell not onto the road but into the river. As the bridge swung up – I swung up with it, and pendulummed back and forth like Paul Kaley on his lamp-post, before losing my grip and plunging down towards the brown depths of the River Hull.

I never reached them, by the way, but always woke up, sweating and terrified, just before the fatal immersion.

This recurred for many years, even after my family traveled twelve thousand miles around the globe to live among the green hills of New Zealand.

And there, gradually, it faded away.

Two fascinating prospects were available as you crossed North Bridge, and one of them had been created at the express wish of Adolf Hitler.

Behind a long street of impressive Georgian houses leading to the city centre – there was nothing but acre upon acre of weed-strewn ruins stretching as far as the eye could see. This was the Luftwaffe’s contribution to urban planning in Hull which, conveniently close to Germany across the North Sea had become one of the German air force’s most popular bombing places during World War Two.

But the effect was not depressing. On the contrary, Hitler had given Hull a great feeling of space, almost of lightness. Behind every wall, it seemed, was a surprise. My favourite was some kind of tabernacle, where the charred remains of the seats in steeply raked tiers rose like a Greek amphitheatre into the roofless sky, populated by a lost an ghostly congregation mouthing silent hymns of praise or possibly lamentation.

To the left of the bridge was a very different prospect. A world of medieval alleys with names like Dagger Lane and Land of Green Ginger, buildings of rosy, time-eroded bricks from the seventeenth century, and dark taverns in which the respectable burgesses of Hull had once plotted against the King of England. A process which ended with his beheading, in Whitehall, by Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan backers.

These lanes ran alongside the river, and many of the houses had their own private wharfs and staithes. In one of them, a hundred and fifty years before I was born, lived William Wilberforce who almost single-handedly took on the most powerful and ruthless corporations of his time to destroy one of their most lucrative business activities – the slave trade.

Wilberforce was a tiny man, a shrimp, they used to say: but when he rose to speak in parliament he seemed to become a leviathan, a great whale of a personality rising from the depths of moral indignation to confront a monstrous evil. And after years of campaigning he persuaded Britain to outlaw the capture and transportation of slaves and cut that evil off at the root.

William Wilberforce resided in a glass case in the hallway of his family home, a handsome seventeenth century merchants’ house, surrounded by relics of the trade he’d abolished: a wax image of himself, it’s true, but so lifelike, his head turned so eagerly as if to catch whatever you wanted to say to him, that it was just as if he was really there, and I never liked to pass his house without calling in to say hello.

Beyond Wilberforce lay Whitefriargate – named after the white-robed medieval monks whose monastery once stood on the site – and a golden statue of King William the Third dressed as a Roman emperor, riding a horse, the sculptor responsible for which, my grandfather assured me, had hanged himself when he realised he’d forgotten to add the stirrups, a story which it never occurred to me to doubt until I learned that the Romans had never invented the stirrup.

Part II

This piece of information, revealing that the sculptor had made no mistake at all, added to the realization that it would have been perfectly easy for him to have put the stirrups in afterwards if he’d wanted, caused me in later years to feel a certain doubt about this tale. But literal truth, of course, was not its real point. It was a fable about the artistic temperament and where it could lead you if you gave way to it. Hull was never a city with a great enthusiasm for the artistic temperament.

But it did like jokes, the earthier and more practical the better, and if you went past the Fisherman’s Church and down Dagger Lane and through the old market you would find yourself in the dim, mysterious recesses of Ferens Arcade in front of a magic cavern known as The Joke Shop, replete with everything the heart of a boy could desire. Just standing outside it was enough to make you feel you were in the centre of the universe, because the window, glowing in the gloom of the arcade, was packed with so many objects of wonder, that you ceased to ask yourself “which of them shall I buy today?” and just basked in your sheer proximity to them.

Where else could you be in the presence, separated only by a sheet of glass, of The Mystic Envelope, (Producing an Amazing Variety of Magical Effects)? Or be able to judiciously weigh the merits of The Paper Tearing Enigma (Gets Them Every Time) against those of the The Trick Cigarette, The Disappearing Pips, the Magic Nail Through Finger, the Double Sided Sucker or the Cake of Black Hand Soap?

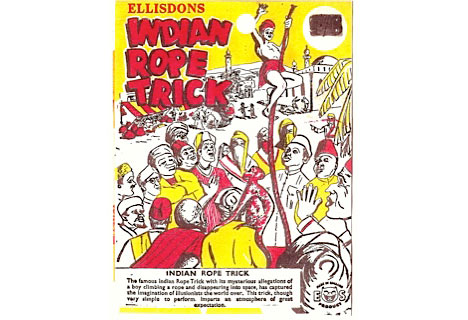

Where else could you gaze to your heart’s delight on The Puffing Sailor (Cleverest Novelty For Years, Uncanny, Unbelievable), The Jolly Golly (Full Directions Enclosed) Sexy Anna, the Beach Girl (The Bachelor’s Delight), the Joke Beetle (Endless Innocent Fun), the Bottle Imp, (Will Not Lie Flat, Can Be Examined) The Magic Bottle Diver (A Wonderful Novelty) the Wine into Water Illusion (Equally Suitable for Stage or Party) the Afghan Band (A Startling Paper-Cutting Mystery) or The Indian Rope Trick – described, in the language shaped by Shakespeare and Milton, as “Simple But Creating an Atmosphere of Great Expectation”.

I think the words describing the Indian Rope Trick could also be applied to my childhood in Hull, because although it was simple it did indeed create an atmosphere of Great Expectation.

It’s hard for me to say whether Hull was any more or less interesting a place to grow up than other large, industrial city in Britain or indeed anywhere in the western world: but it had the capacity, with its fogs and trolley buses and mysterious alleyways and ruined vistas and heroes in glass cases to produce Great Expectation.

It is an atmosphere, when I think of it, which has continued to envelop me ever since.

No Comments