13 Feb Beloved Books

From my earliest childhood certain prospects and memories have filled me with such delight that bringing them to mind is finding oneself unexpectedly before a bright and blazing fire.

on a dark winter’s afternoon. During the course of a lifetime of reading I have come across passages in literature which have ignited that delight so spontaneously once read they are never forgotten.

This is the beginning of a collection of some of those pleasures with, when I’ve got time, notes on why they work so well. More to follow.

LEAVETAKING

It seems appropriate to start with a young man setting out on a journey: and what a journey!. Patrick Leigh Fermor’s “A Time of Gifts” is one of the great travel books. In 1933, at the age of eighteen, Leigh Fermor set off on an apparently absurd quest to walk from London to Constantinople, sleeping in castles and barns along the Rhine and the Danube all the way to Hungary, where the first volume of his travels ends. The title refers to the generosity he met along the way, as if his quixotic plan somehow revived the youthful dreams of almost everyone he encountered. He was delighted with everything he saw: his numerous hosts were delighted with him.

It seems appropriate to start with a young man setting out on a journey: and what a journey!. Patrick Leigh Fermor’s “A Time of Gifts” is one of the great travel books. In 1933, at the age of eighteen, Leigh Fermor set off on an apparently absurd quest to walk from London to Constantinople, sleeping in castles and barns along the Rhine and the Danube all the way to Hungary, where the first volume of his travels ends. The title refers to the generosity he met along the way, as if his quixotic plan somehow revived the youthful dreams of almost everyone he encountered. He was delighted with everything he saw: his numerous hosts were delighted with him.

The entire book is a source of great pleasure, allowing the reader to slog through winter storms and stroll through sunlit meadows of a Europe that has now vanished: and the passage I have chosen is a brilliant demonstration of Leigh Fermor’s superb control over the English language. Before I talk about why I like it so much, and what other associations it brings, here it is: A Time of Gifts, Chapter One.

FROM: A TIME OF GIFTS

BY PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR

“A splendid afternoon to set out!”, said one of the friends who was seeing me off, peering at the rain and rolling up the window.

The other two agreed. Sheltering under the Curzon Street arch of Shepherd Market, we had found a taxi at last. In Half Moon Street, all collars were up. A thousand glistening umbrellas were tilted over a thousand bowler hats in Piccadilly; the Jermyn Street shops, distorted by streaming water, had become a submarine arcade; and the clubmen of Pall Mall, with china tea and anchovy toast in mind, were scuttling for sanctuary up the steps of the clubs. Blown askew, the Trafalgar Square fountains twirled like mops, and our taxi, delayed by a horde of Charing Cross commuters reeling and stampeding under a cloudburst, crept into the Strand. The vehicle threaded its way through a flux of traffic and splashed up Ludgate Hill as the dome of St Paul’s sank deeper its pillared shoulders. The tyres slewed away from the drowning cathedral and a minute later the silhouette of The Monument, descried through veils of rain, seemed so convincingly liquefied out of the perpendicular that the tilting thoroughfare might have been forty fathoms down. The driver, as he swerved wetly into Upper Thames Street, leaned back and said: ‘Nice weather for young ducks.’

A smell of fish was there for a moment, then gone. Enjoining haste, the bells of St Magnus the Martyr and St Dunstans‑in‑the East were tolling the hour; then sheets of water were rising from our front wheels as the taxi floundered on between The Mint and the Tower of London. Dark complexes of battlements and tree‑tops and turrets dimly assembled on one side; then, straight ahead, pinnacles and the metal parabolas of Tower Bridge were looming. We halted on the bridge just short of the first barbican and driver indicated the flight of stone steps that descended to Irongate Wharf. We were down them in a moment; and beyond the cobbles and the bollards, with the Dutch tricolour beating damply from her poop and a ragged fan of smoke streaming over the river, the Stadthouder Willem rode at anchor. At the end of lengthening fathoms of chain, the swirling tide had lifted her with a sigh almost level with the flagstones: gleaming in the rain, and with full steam‑up for departure, she floated in a mewing circus of gulls. Haste and the weather cut short our farewells and our embraces and I sped down the gangway clutching my rucksack and my stick while the others dashed back to the steps ‑ four sodden trouser‑legs and two high heels skipping across the puddles ‑ and up them to the waiting taxi; and half a minute later there they were, high overhead on the balustrade of the bridge, craning and waving from the cast‑iron quatrefoils. To shield her hair from the rain, the high‑heel‑wearer had a mackintosh over her head like a coalheaver. I was signalling frantically back as the hawsers were cast loose and the gangplank shipped. Then they were gone. The anchor‑chain clattered through the ports and the vessel turned into the current with a wail of her siren. How strange it seemed , as I took shelter in the little saloon ‑ feeling, suddenly, forlorn; but only for a moment ‑ to be setting off from the heart of London! No beetling cliffs, no Arnoldian crash of pebbles. I might have been leaving for Richmond, or for a supper of shrimps and whitebait at Gravesend, instead of Byzantium. Only the larger ships from the Netherlands berthed at Harwich, the steward said: smaller Dutch craft like the Stadthouder always dropped anchor hereabouts: boats from the Zuider Zee had been unloading eels between London Bridge and the Tower since the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Miraculously, after the pitiless hours of deluge, the rain stopped. Above the drifts of smoke there was a quickly‑fading glimpse of restless pigeons and a few domes and many steeples and some bone‑white Palladian belfries flying rain‑washed against a sky of gunmetal and silver and tarnished brass. The girders overhead framed the darkening shape of London Bridge; further up, the teeming water was crossed by the ghosts of Southwark and Blackfriars. Meanwhile St Catherine’s Wharf was sliding offstage and upstream, then Execution Dock and Wapping Old Stairs and The Prospect of Whitby and by the time these landmarks were astern of us, the sun was setting fast and the fissures among the western cloudbanks were fading from smoky crimson to violet. In the gulfs spanned by catwalks between the warehouses, night was assembling too, and the tiers of loading‑loopholes yawned like caverns. Slung with chains and cables weighted with shot, hoists jutted on hinges from precipices of warehouse wall and the giant white letters of the wharfingers’ names, grimed by a century of soot, were growing less decipherable each second. There was a reek of mud, seaweed, slime, salt, smoke and clinkers and nameless jetsam, and the half‑sunk barges and the waterlogged palisades unloosed a universal smell of rotting timber. Was there a whiff of spices? It was too late to say: the ship was drawing away from the shore and gathering speed and the details beyond the wider stretch of water and the convolutions of the gulls were growing blurred. Rotherhithe, Millwall, Limehouse Reach, the West India Docks, Deptford and the Isle of Dogs were rushing upstream in smears of darkness. Chimneys and cranes plumed the banks, but the belfries were thinning out. A chaplet of lights twinkled on a hill. It was Greenwich. The Observatory hung in the dark, and the Stadthouder was twanging her way inaudibly through the nought meridian.

The reflected shore lights dropped coils and zigzags into the flood which were blown into disarray every now and then by the silhouettes of passing vessels’ luminous portholes, the funereal shapes of barges singled out by their port and starboard lights and cutters of the river police smacking from wave to wave as purposefully and as fast as pikes. Once we gave way to a liner that towered out of the water like a festive block of flats; from Hong Kong, said the steward, as she glided by; and the different notes of the sirens boomed up and downstream is though mastodons still haunted the Thames marshes.

A gong tinkled and the steward led me back into the saloon. I was the only passenger. ‘We don’t get many in December,’ he said; ‘It’s very quiet just now.’ When he had cleared away, I took a new and handsomely‑bound journal out of my rucksack, opened it on the green baize under a pink‑shaded lamp and wrote the first entry while the cruets and the wine bottle rattled busily in their stands. Then I went on deck. The lights on either beam had become scarcer but one could pick out the faraway gleam of other vessels and estuary towns which the distance had shrunk to faint constellations. There was a scattering of buoys and the scanned flash of a light‑house. Sealed away now beyond a score of watery loops, London had vanished and a lurid haze was the only hint of its whereabouts.

I wondered when I would be returning. Excitement ruled out the thought of sleep; it seemed too important a night … But I must have dozed, in spite of these emotions, for when I woke the only glimmer in sight was our own reflection on the waves. The kingdom had slid away westwards and into the dark. A stiff wind was tearing through the rigging and the mainland of Europe was less than half the night away.

It was still a couple of hours till dawn when we dropped anchor in the Hook of Holland. Snow covered everything and the flakes blew in a slant across the cones of the lamps and confused the glowing discs that spaced out the untrodden quay … This solitary entry, under cover of night and hushed by snow, completed the illusion that I was slipping into Rotterdam, and into Europe, through a secret door.

That “slipping into Europe through a secret door”. What a wonderful touch! The secret doors so beloved of children, entrance to some enchanted kingdom. But the enchantment is there right from the beginning, as the taxi sets off through a London downpour. Jermyn Street becoming a “submarine arcade”, for example, conjuring vistas of sea-caves glistening with treasure, and the Monument – that obelisk memorialising the Great Fire of London – distorted by the rain as if the street was “forty fathoms down”.

*Two links here: one with arcades, which have a magic all their own, especially in relation to the rain, and another with drowned cities. We’ll get to them.

Did you notice Leigh Fermor’s wonderful note that the ship he’s sailing on has been raised by the tide so he can step straight onto it from the cobbles? Like an illicit pleasure? He’s right: it is a special privilege to step right out of the middle of a city straight into foreign adventure without the normal paraphenalia of airports and station platforms and distant docks. It’s like finding that secret door.

*There’s a link here to the paintings by Claude Lorrain: we’ll pick it up later.

I realise also that this passage contains a key to why this whole passage pleases me so much: it’s about departure. Secret departure. Slipping away right from the middle of things.

*This links to Great Departures of my own: starting with the moment in March 1961 when my family boarded a train in Paragon Station in the city of Hull in Yorkshire to set out on a voyage halfway round the world to New Zealand. Further details further on.

Back to Leigh Fermor, now on his ship heading down the Thames – and his evocation of the coming of night: “fissures among the western cloudbanks fading from smoky crimson to violet”. That word “fissures” – making us think of the gaps between the clouds as canyons, of the clouds themselves as mountains. Even the phrase “western cloudbanks” has a resonance of its own – it reminds us of “the western approaches” and all those other names for distant but strangely familiar parts from distant time, like “the Saxon shore” and “the Spanish Main”.

*Let’s have a look at romantic geographical terms in another place, and make sure we deal with “The German Bight” and “the fall line” and “sea-islands”.

Back to Fermor: he hits another perfect note right after the reference to the cloudbanks: “in the catwalks between the warehouses night was assembling too.” There’s something pleasingly bleak about the image of the iron catwalks between the grim, soot-blackened warehouses that makes the cosiness of being inside the boat even cosier. For me they bring to mind “Oliver Twist” and the steel-engravings of Bill Sykes fleeing across the rooftops of London with the crowd chasing him in the canyons below.

But back to the cosiness of Leigh Fermor aboard ship: not only the pleasure of being the only passenger “We don’t get many in December” but the satisfaction of taking out his “handsomely bound journal” and laying it out on the green baize table “under a pink-shaded lamp”. What better antidote to the gathering dark outside than that “pink-shaded lamp”? And the final touch: when he arrives in Holland, “snow covered everything … on the untrodden quay” and he’s able to pass silently and unseen through that secret door into the continent.

There’s another interesting point about this passage: Leigh Fermor juggles brilliantly with feelings of comfort surrounded by hostile elements (the taxi through the rainstorm, the glowing boat through the darkness) and in doing so he stimulates our own feelings of comfort at being in a comfortable chair, or a warm bed, reading about his exploits. Contained within the pages of the book we’re holding are snowstorms and miles of empty road and nights on bare mountains; but we’re safely on the outside. We’re the comfort that contains the discomfort: a neat reversal of the situation of the author as he slogs, on our behalf, across a Europe over which Hitler’s shadow was just beginning to fall.

ANOTHER LEAVE-TAKING

Here’s another scene of departure: this time from J. R. R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings”. Frodo Baggins, having learnt from the wizard Gandalf that the all-powerful Ring of Sauron must be got out of the Shire as soon as possible, decides, with reluctance, to leave his beloved home, Bag End – initially for a new house on the far side of the land of the hobbits. This extract is from the third chapter: Three Is Company.

Here’s another scene of departure: this time from J. R. R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings”. Frodo Baggins, having learnt from the wizard Gandalf that the all-powerful Ring of Sauron must be got out of the Shire as soon as possible, decides, with reluctance, to leave his beloved home, Bag End – initially for a new house on the far side of the land of the hobbits. This extract is from the third chapter: Three Is Company.

FROM: THE LORD OF THE RINGS

BY J. R.R.R TOLKIEN

The sun went down. Bag End seemed sad and gloomy and dhishevelled. Frodo wander round the familiar rooms, and saw the light of the sunset fade on the walls and shadows creep out of the corners. It grew slowly dark indoors….They shouldered their packs and took up their sticks and walked round to the west side of Bag End. “Goodbye”, said Frodo, looking at the dark blank windows. He waved his hand and then turned and, (following Bilbo, if he had known it) hurried after Peregrin down the garden path. They jumped over the low place in the hedge at the bottom and took to the fields, passing into the darkness like a rustle in the grasses… They went in single file along hedgerows and the borders of coppices and night fell dark around them. After some time they crossed the Water, west of Hobbiton, by a narrow plank bridge…Then they struck south east and began to climb into the Green Hill Country to the south. They could see the village twinkling down in the gentle valley of the water. Soon it disappeared in the folds of the darkened land, and was followed by Bywater beside its grey pool. “I wonder if I shall ever look down into that valley again,” said Frodo quietly.

The night was clear, cool and starry, but smoke-like wisps of mist were creeping up the hillsides from the streams and deep meadows….they marched in silence, and Pippin began to lag behind. “Are you going to sleep on your legs?” he asked. “It’s nearly midnight.” Just over the brow of the hill they came to a patch of fir-wood and went into the deep resin-scented darkness of the trees to collect sticks and cones to make a fire by a large fir-tree. Then, each in an angle of the trees great roots they curled up in their coats and blankets and were soon fast asleep. A few creatures came and looked at them when the fire had died away. A fox passing through the wood on business of his own stopped several minutes and sniffed. “Hobbits,” he thought. “Well, what next? I have heard of strange doings in this land but never of a hobbit sleeping out of doors under a tree. Three of them! There’s something mighty queer about this!” And he was quite right – but he never found out any more about it.

LONDON CAUGHT IN WORDS

Here’s a description of the kind of corner of London that you come across, unexpectedly, if you spend any time at all walking in the city: usually, in my experience, in the middle of a rainstorm. But this time, in Chapter Two of Margery Allingham’s classic detective novel “Tiger in the Smoke” – in thick fog.

FROM: TIGER IN THE SMOKE

BY MARGERY ALLINGHAM

The fog was thicker than ever over in St Petersgate Square … cosy, hardly cold, gentle, almost protective. The little close was well hidden even on the brightest of days. Then years before even the bombers of Luftwaffe had not found it and so, almost alone in the district, the quiet houses remained just as they had always been. By yet another oversight the railings round the tiny square in the centre had been spared by the scrap merchants, and the magnolia, two or three graceful laburnams and a tulip tree had overgrown unmolested. It was one of the smallest squares of its kind in the city. There were several houses on each of the two opposite sides, a wall on the third which shut out the steep drop into Portminster Row and the shops, and on the fourth, the sharp-spired church of St Peter of the Gate, its recotry and two minute glebe-cottages adjoining. The square was a cul-de-sac. The only road led in by the wall so that all wheeled traffic had to return by the way it had come, but for foot passengers only there was a flight of steps at the other end … worn and highly dangerous despite the bracket street lamp on the churchyard wall. There were lights in every window of the rectory, and the two which flanked the squat porch glowed red and warm-looking in the mist, but with visibility on the road below almost down to nil, the rectory might have been alone upon a moor.

The fog was thicker than ever over in St Petersgate Square … cosy, hardly cold, gentle, almost protective. The little close was well hidden even on the brightest of days. Then years before even the bombers of Luftwaffe had not found it and so, almost alone in the district, the quiet houses remained just as they had always been. By yet another oversight the railings round the tiny square in the centre had been spared by the scrap merchants, and the magnolia, two or three graceful laburnams and a tulip tree had overgrown unmolested. It was one of the smallest squares of its kind in the city. There were several houses on each of the two opposite sides, a wall on the third which shut out the steep drop into Portminster Row and the shops, and on the fourth, the sharp-spired church of St Peter of the Gate, its recotry and two minute glebe-cottages adjoining. The square was a cul-de-sac. The only road led in by the wall so that all wheeled traffic had to return by the way it had come, but for foot passengers only there was a flight of steps at the other end … worn and highly dangerous despite the bracket street lamp on the churchyard wall. There were lights in every window of the rectory, and the two which flanked the squat porch glowed red and warm-looking in the mist, but with visibility on the road below almost down to nil, the rectory might have been alone upon a moor.

The perfect setting for the saintly Canon Avery and his beautiful daughter to be stalked by the most dangerous man in London – with the prospect of medieval treasure lurking in the background.

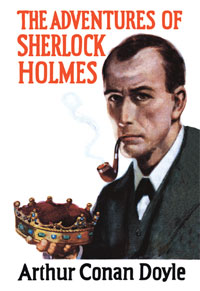

THE ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

I plunged into the world of Sherlock Holmes at the age of ten, starting with The Adventures. In Hull with long-saved pocket money I first bought a wonderful John Murray paperback with an evocative red and yellow cover; then I saw this edition in the window of a Christian bookstore opposite The People’s Palace in Cuba Street, Wellington, New Zealand, a Salvation Army hotel where my family stayed when we first arrived as emigrants to New Zealand in 1961. I determined that one day I’d own that edition, and many years later, long after it was out of print, tracked down it and its companion volumes with their equally striking covers. And of course, inside, there was the wonderful, atmospheric,sometimes scarifying but ultimately deeply comforting world of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. “The game’s afoot!”

I plunged into the world of Sherlock Holmes at the age of ten, starting with The Adventures. In Hull with long-saved pocket money I first bought a wonderful John Murray paperback with an evocative red and yellow cover; then I saw this edition in the window of a Christian bookstore opposite The People’s Palace in Cuba Street, Wellington, New Zealand, a Salvation Army hotel where my family stayed when we first arrived as emigrants to New Zealand in 1961. I determined that one day I’d own that edition, and many years later, long after it was out of print, tracked down it and its companion volumes with their equally striking covers. And of course, inside, there was the wonderful, atmospheric,sometimes scarifying but ultimately deeply comforting world of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. “The game’s afoot!”

No Comments