20 May The Age of Treachery

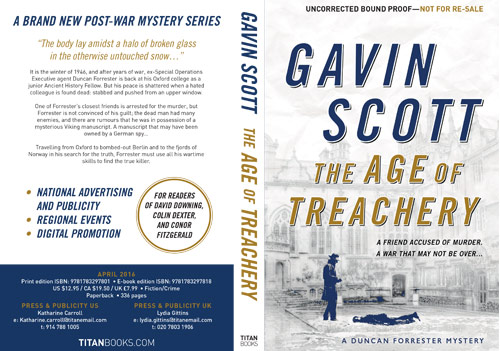

I’m pleased to announce that on April 16th 2016 Titan Books in the UK and Random House in the US are publishing the first in my series of detective thrillers about Duncan Forrester, former SOE operative and ancient historian whose adventures, starting in 1946, will chronicle the creation of the postwar world.

As the book begins, Duncan Forrester, having spent six years in the most dangerous actions of the war against Hitler, is back in war-weary Britain. All he wants to do is forget the terror and the tragedy and get back to studying ancient history in his Oxford College. But when a fellow don is found dead and his best friend is accused of the crime, Forrester finds himself plunged into a mystery involving Satanism, Icelandic sagas and war-time treachery that could change the course of Britain’s future. In his quest for the truth Forrester finds himself up against the people who shaped the world we live in: Tolkien before Lord of the Rings, Margaret Thatcher before she was Margaret Thatcher, Thor Heyerdahl before Kon Tiki, Ian Fleming before James Bond. And has to face terror and death in the ruins of Berlin and the forests of Norway before he uncovers the extraordinary truth about what really happened.

*

CHAPTER ONE

THREE LUMPS OF COAL

The snow had been falling since noon, and Forrester brushed urgently at the graveyard bench to clear a space to sit down before the vertigo overcame him. The world continued to spin for a moment after he sat down, but then the silence began to seep into him, and he felt his heart slow.

The buildings around the graveyard were mostly Georgian, and the snow was piling up on the deep ledges of their tall windows. The church and its adjoining houses shut the burial ground off from the bustle of the city, and Forrester felt safe, as if he was in a tiny clearing in a dense, silent wood.

There were few cars in Oxford just after the war, and little fuel for them anyway, so what noise there was mostly came from footsteps in the street beyond, and even they were muffled. As the snow came down and the light leaked out of the afternoon, Forrester closed his eyes and waited for the demons to slip away into the gloom.

He could not banish them; he’d tried that. The only method that worked was to let the images rise to the surface without trying to stop them. As they passed through his conscious mind he felt the familiar wave of nausea; but he forced himself to ride it, reminding himself these things were no longer realities, that they would fade.

He felt again the peculiar gliding sensation as the knife passed through the cartilage of the sentry’s throat; he smelt the youth’s skin as he gripped him, and then the warmth of the blood as it poured over his fingers and the body slid down to his feet, looking up at him with mildly reproachful eyes. Forrester guessed he was about seventeen. As the sentry died Forrester could see, through the archway leading to the castle courtyard, SS officers taking the prisoners into the Great Hall.

There were many such images. He let them unreel at their own speed.

He saw Barbara again too, that last time at Waterloo Station, and the look in her eyes that made him think of Arctic winds blowing over a wasteland of ice.

He did not see the man watching him from the tall, unlit window on the far side of the graveyard. But the man was aware of the Forrester’s posture, the set of his shoulders, the tilt of his head, and long experience allowed to make remarkably shrewd guesses as to what was happening in Forrester’s mind.

For a long time, both men were motionless, separated by no more than fifty yards of snow and lichened stone, and as the watcher registered Forrester’s breathing return to normal he could almost see, through the young ex-serviceman’s eyes, the snow turning the gravestones turned into shapeless white mounds.

Suddenly, from the archway that led to the street, Forrester heard the word “vintersolstånd” followed by laughter, and then a brief babble of Swedish before the speakers passed on down the street. There were students from all over Europe in Oxford now, a flood pent up by the war, released by the peace. They were not the high young voices of his own university years, but deeper, more mature. Many of the British undergraduates in Oxford now were ex-servicemen, their education postponed by the war. They too poured in, thirsty for knowledge.

Duncan Forrester had graduated before the war began, and now, just months after the German surrender, he was back as a Fellow of his college. But though he was still in his twenties, he felt bone tired, as if he was an old man.

He held out his hand and watched the snowflakes settle on it. As the heat of his body turned them to water, the drops rolled into his palm like a tiny pool. By the time he realised his hand was numb with cold he was calm again.

He paused a moment, savouring the calm, and went through the ritual. He was alive; he was in one piece; the war was over; he was back in Oxford; he was free to pursue his researches. Images of Barbara came and went, but all they evoked now was remembered pain – and deep behind that, remembered joy, like a distant Eden.

The man in the window watched as Forrester rose to his feet, shook the whiteness off him, tightened the belt of his British Warm overcoat, headed back through the archway into the street, and disappeared. Only then did the watcher switch on the light inside the room, letting it spill over the empty churchyard like liquid gold.

Moments later he closed the curtains, plunging the graveyard back into darkness.

Among the crowds in the street, Forrester felt almost normal again, just one of the many going to the shops on their way home from work. Not that there was much to buy, for this was austerity Britain, a victorious nation ruined by the struggle for victory.

“Cadbury’s Milk Chocolate is the Best” proclaimed a poster showing the familiar maroon and gold wrapper so evocative of pre-war pleasures. Then in smaller letters below the advertisers announced “Unfortunately we are only allowed enough milk to make extremely small quantities of our famous product, so if you are lucky enough to get some, do save it for the children.”

But Forrester, who had not seen a piece of chocolate for at least a year, knew no children to save it for. He glanced into the brightly lit interior of Woolworths, an Aladdin’s cave of gaudy trinkets before the war, now full of half empty glass counter-trays scattered with a sparse collection of wooden pegs, darning needles and penny notebooks. Outside a grocery shop a notice announced a limited supply of dried egg powder and a queue was already forming.

Forrester gave a wry grin: for most of the war people had had to rely on dried eggs instead of the real thing – and they had hated them. Cakes made with egg powder had the texture of old cement; when mixed with water and fried, the powder turned into luridly yellow leather pancakes.

And then, with victory, not only did fresh eggs not re-appear – but dried egg powder itself vanished: unavailable until Britain could borrow more money from the Americans. So women were now lining up patiently with their string bags, shivering in the cold, desperate for a product they had despised for five years.

And this was what happened when you won.

A woman darted out of the queue – which closed up immediately behind her – and turned towards Forrester. He raised his hat automatically before he realised that not only was she not coming towards him, she hadn’t even seen him.

Her name was Margaret Clark and Forrester thought she was, perhaps the most desirable woman in Oxford: a thought he tried to suppress because she was also the wife of his closest friend. And though her eyes were bright with affection as she turned towards him, he knew the affection wasn’t for him – her gaze was fixed on someone on the far side of the road.

As a result of which she stepped right off the curb and into the path of an oncoming bus.

Forrester shouted a useless warning and stepped equally uselessly into the road after her – as the bus swerved and sent up a spray of grey slush. The slush momentarily blinded him and when he had cleared it away the bus was gone and Margaret Clark had disappeared. But to his astonishment no blood stained the snow; no crushed body lay in the road. The bus had missed her. He peered at the crowd across the road – but she had vanished as if she had never been.

“Got something for you, Dr. Forrester,” said Harrison, materializing at his elbow, a pipe clamped between his teeth. Forrester blinked at him and then remembered.

“Delian League?”

“Oh, that,” said Harrison, dismissively. “No, much better.” He was a cheerful, stocky young man of twenty four, who had been trying furiously to get a faulty field radio to work when he was captured at Arnhem and taken as a POW to Germany – an experience which seemed to have no mark at all on his sunny disposition. Forrester was tutoring him in Greek history.

“Better than one of your essays?” said Forrester.

“That wouldn’t be hard,” said Harrison equably. Both he and Forrester were well aware that Harrison’s essays scaled no heights of brilliance, but Harrison was as unperturbed about that as he seemed to be about all the vicissitudes life threw his way.

They passed under the worn stone archway of Barnard College, past the porter’s cubbyhole with its tabby cat and ticking clock and pigeonholes full of messages, and entered the first quadrangle. The snow lay thick on the famous lawn and the Great Hall and the Lady Tower, festooned with scaffolding where builders, under the impatient supervision of Alan Norton, were slowly – very slowly – repairing the damage done when it had been an air raid warden’s observation post during the war. Undergraduates and fellows hurried back to their rooms along the cloisters as the light leaked out of the sky and the afternoon turned to evening.

Forrester and Harrison scraped the snow off their feet and clumped up the narrow wooden stairs to Forrester’s rooms. The air struck cold as he knelt down by the fireplace and fiddled with the matches; Harrison reached into the canvas army detonator satchel he used as a bookbag, pulled out something wrapped in newspaper and gave it to him. Forrester read the headlines on the paper as he took off the wrapping.

“Iron Curtain Falling Across Europe Says Churchill”

Inside were three lumps of coal.

“Where did you get these?” Forrester said, and immediately added “Actually I don’t want to know,” and put the lumps on the fire. “But it’s very kind of you. Thanks.”

Coal was another item Forrester had not seen enough of since he came back from the war. But Harrison had a knack for getting his hands on these things. Perhaps that was what he had learnt in the German camps.

They both kept their coats on in the frigid air as the fire took hold and Harrison took out his essay and began to read. And by the time the flames were sending out any heat both men were far away, on the plains of Athens in the golden age of Greece, with the sun glinting off the marble of the Acropolis.

Outside, around the college, one window after another began to glow with yellow light like the opening doors of an Advent calendar.

*

The fire was dying down by the time Harrison left, and Forrester took a shovel full of ashes and banked it down to preserve the coal. The warmth in the room would last until it was time to go to Hall for the evening meal. Then he took the photographs from the desk drawer and began to look at them again. They were very bad photographs; or rather, infuriatingly imperfect for his purposes, showing small rectangles of clay, thickly inscribed with symbols and stick figures, for all the world like the message in the Sherlock Holmes story “The Five Orange Pips”.

Here and there you could make out a drawing which might be a horse’s head, and another which looked like a double-bladed axe, but most of the letters were as indecipherable as if they had been written by the inhabitants of another planet. The script was known as “Linear B” and the tablets on which it was inscribed had been baked in the heat of the fire which had destroyed the palace at Knossos in Crete a thousand years before Athens rose to glory. No-one had been able to decipher the tablets since Sir Arthur Evans discovered them: and Forrester suspected that some of Evans’ guesses had put people on the wrong track.

For example, what if the old man had been wrong about the significance of the symbol that looked like a double-bladed axe? What if it did not in fact signify a religious ritual, but was actually a phonetic indicator? He turned to the drawings Evans had made of other inscriptions, and wondered how accurate they really were.

“You’re busy,” said a voice. Forrester looked up to see Barnard’s Senior Tutor Gordon Clark looking round his door. For a moment he was tempted to say “I am a bit busy, actually, old chap,” and turn back to the tablets, but when he saw Clark’s white, strained face he knew he could not.

“Absolutely not,” he said. “Come in and have some sherry.”

“Thank you,” said Clark, and closed the door. He entered the room nervously, glancing into the shadows as though looking for a hidden observer.

Forrester, pouring the sherry, made the embarrassing discovery that the bottle was almost empty. He thought of dividing the liquid between both glasses and decided against it. With his back to Clark he filled his own glass with cold tea before he handed the full one to his friend.

“Your health,” he said, and Clark nodded and sank back into a chair on one side of the fire. Forrester reached in with the poker and stirred it into to life.

“Any progress?” said Clark, nodding towards the work table.

“I’m not at the progress stage yet,” said Forrester. “I have to dig myself in much deeper before I can start digging my way out.” He sipped his glass of cold tea with every appearance of appreciation. “I saw Margaret in Broad Street this afternoon. I think she’d just given up queuing for egg powder.”

He waited for Clark to tell him that it was he, her husband, she’d been running across the road to see, but the Senior Tutor just nodded and looked into the fire. Finally he said “Have you ever understood them, Forrester?” When Forrester did not reply, Clark said “Women, I mean.”

“Good Lord, no,” said Forrester. It was not what he felt, it was not what he believed: but it was what Clark needed to hear. “But surely a married man has a better chance than most?”

“You’d think so, wouldn’t you?” Clark sipped the sherry, but Forrester knew he could have given him the cold tea and the Senior Tutor wouldn’t have noticed. Suddenly Clark looked up, his eyes hot with pain. “She used to love me, you know.”

“I’m sure she still does,” said Forrester, with a strange sinking feeling in his stomach.

“No,” said Clark “She’s found someone else.”

Again, Forrester decided silence was the best response. His own suppressed feelings for Margaret Clark made it almost impossible to make the right comforting remarks.

“And you know the worst part of it?” said Clark. “I feel … slighted – ”

“Well, of course – ”

“By who she’s chosen,” said Clark. Forrester held his breath as he waited for Clark’s elucidation. “David bloody Lyall.”

“That’s ridiculous,” said Forrester, automatically, quick to cover his own swift stab of jealousy: but in truth he was not in the least surprised at Margaret Clark’s choice. Lyall was handsome, self-confidant and stylish. He was ambitious and successful: he’d leapt ahead of several other abler candidates for a fellowship and was a serious candidate for the Rotherfield Lectureship. But Forrester understood why Clark felt slighted, because both men knew that Lyall was also shallow, meretricious and glib: a showy scholar without real insight, not in Clark’s league. But scholarship, of course, was not what Margaret had been looking for.

“I always used to look down on Latins, you know,” said Clark. “All that passion and jealousy. It seemed so self-indulgent. But I tell you, Forrester, I could cheerfully strangle that little swine.”

“It would probably do him good,” said Forrester, and despite himself, Clark laughed.

“Unfortunately they didn’t teach us much about unarmed combat at Bletchley,” said Clark.

Clark’s war had been spent working on signals which had been encoded in the German Enigma machines: he had been in no physical danger, but Forrester knew his mind had been almost worn out by the effort. He hadn’t slept, sometimes, for a week at a stretch, so desperate was the race to decipher the German army’s field commands fast enough for Allied troops to make use of the intelligence. Clark had told Forrester, when he was helping him with his application for the Rotherfield Lectureship, that his mind felt strained, like a damaged muscle, and he wasn’t sure if it would ever be back to its full strength again.

Forrester knew that since the war Clark had lived on his nerves, strung out like a taut wire. He wondered what effect Margaret’s affair would have on him.

“As someone who was taught unarmed combat,” said Forrester, “I can tell you I don’t recommend its use in polite society.”

“Not even in special circumstances?” asked Clark.

“This Lyall thing’s an infatuation,” said Forrester. “It’ll pass.”

“How do you know?”

“Because Lyall is a complete second rater, you are a man of real worth and Margaret is an intelligent woman,” replied Forrester decisively. “She’ll see through him before long.”

“And I should just hang about until she does?”

“I don’t know,” said Forrester. “I can’t advise you there. All I’m saying is don’t do anything precipitate.”

“Like sticking a knife in his heart?”

“I think that would qualify as precipitate.”

“I’ve got to sit at High Table with the swine.”

“Ignore him. Sit at the other end. If you catch his eye regard him with cold contempt.”

Clark grinned ruefully. “Cold contempt, eh?

“Buckets of it. I’ll do the same. He’ll have cold contempt everywhere he turns.”

Clark finished his glass and stood up. “Thank you, old chap,” he said. “I had to tell somebody: I was going out of my bloody head.”

Forrester stood up too. A bell began to toll. “Shall we go down?” Clark hitched his gown around him. “Why not?” he said “I’ve worked up quite an appetite.”

David Griffiths

Posted at 14:45h, 11 MarchI’m looking forward to reading the rest of it.

It reads like a great thriller in the vein of John Buchan, Alistair MacLean and (at his best) Tom Clancy. A fast-moving plot laced with fun characters and interesting locations.

.

Gavin Scott

Posted at 11:33h, 24 MarchHope you enjoy it, Dave.

X

G

Karen Griffiths

Posted at 11:15h, 16 MarchCan’t wait to read on. It’s a perfect choice for my book club and great timing as our next meeting is April 10th.

Gavin Scott

Posted at 11:32h, 24 MarchThanks, Karen: I hope you enjoy it!

X

G

Magne Frostad

Posted at 14:57h, 28 JuneDear Gavin. I have thoroughly enjoyed the three wonderful Duncan Forrester books. Will you be writing a fourth? Best, Magne

Gavin Scott

Posted at 22:05h, 06 JulyThank you for those kind words, Magne. And yes, a 4th Duncan Forrester has been completed. Watch this space!