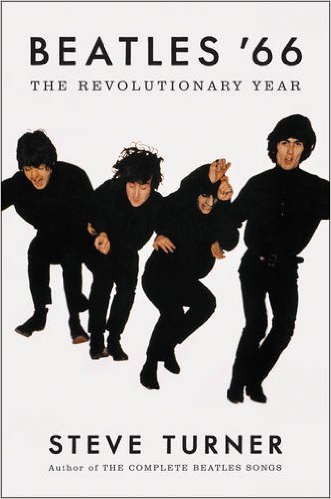

04 Apr The Beatles Revolutionary Year

I’ve just read Beatles ’66, The Revolutionary Year, a terrific book by Steve Turner about what changed the Beatles between December 1965 and December 1966 as they made the leap from Rubber Soul (1965) via Revolver (1966) to the extraordinary achievements of Sergeant Pepper in 1967. On Rubber Soul, Turner points out, 13 of the 14 songs were about love: but on Revolver, 9 of the 14 were about other things entirely, starting, of course, with Taxman. And then came Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields …

Most of the book is a fascinating account of what happened to the Beatles during those 12 months, including their last tour of Britain, the recording and naming of Revolver, the ‘butchered babies’ LP cover, John’s “We’re bigger than Jesus” furore in America, the mob assault in the Philippines and their first, pre-Maharishi visit to India straight afterwards, which I hadn’t heard of. All these go part of the way to explaining what changed them from super-successful pop stars into cutting edge artists who changed the way we all listen to music – but Turner reveals there’s much more.

It started, of course, with their natural talent: a genius for creating memorable pop songs which began with something that sounded familiar but took the listener somewhere unexpected.

Then came their work ethic: despite all their live performances and touring they produced 22 songs in 1963, 26 in 1964 and 35 in 1965.

Next: their boredom with repeating themselves, their determination to try new things – and their ambition as artists. As Paul himself said “We are so well established that we can bring the fans along with us – stretch the limits of pop.”

Turner attributes this to their often dismissed education in Liverpool, usually overshadowed by tales of them bunking off from school and arts college to play music. Paul’s literary studies at the Liverpool Institute included Chaucer, Shakespeare, Sheridan, Wilde, Shaw, Auden and Dylan Thomas, and John’s studies at the Liverpool Arts College immersed him in the world of visual arts. With excellent, inspiring instructors, says Turner, “arts students were usually well ahead of their contemporaries in fashion, musical taste and lifestyle choices” John’s friend Stu Sutcliffe, the Beatle who died young, exemplified this – and was also a truly talented painter. What John and Paul learned during their education, says Turner “enlarged their frame of reference” so when success finally came to them they saw themselves not just as entertainers but as creators in the same tradition as painters, sculptors, film makers, poets, novelists and dramatists. When they talked about their work they included references to Van Gogh, Picasso, Lewis Carroll and William Burroughs. On the cover of Sergeant Pepper the images of people who had influenced them included more than 40 writers, artists and actors – and only 4 musicians.

He speaks of the impact of LSD and other drugs, but pays as much attention to the effect of the well educated families in London with who they came into contact, such as the cultivated parents of Jane Asher, Paul’s girlfriend, and Ayana and Patricia Angadi, who helped George find his way into Indian music, gallery owners like Robert Fraser and thoughtful journalists like Maureen Cleave.

Not to mention George Martin, their producer, who brought them his classical music training as well as his many years of recording experience, “Old enough to earn their respect, young enough to be their friend, sober enough to keep control, wild enough to experiment,” summarises Turner.

Add to that their ability to think conceptually – to imagine a type of song not yet in existence and work their way, with George Martin’s help, towards achieving it, and vastly expanded studio time (Revolver took 225 hours, compared to 10 for Please Please Me) – and you have a hugely powerful combination.

The penultimate ingredient: talented, ambitious competition, of which there was no shortage in 1966: Dylan, the Stones, the Who, the Kinks, the Byrds, the Animals, the Beach Boys, all, like the Beatles, at the top of their game and all jostling to be at the artistic and commercial forefront.

And finally, says Turner, the fact that in 1966 “the tectonic plates of different cultural outlets were grinding against each other, releasing waves of energy the group was able to translate into art.” (What a great, rich compacted sentence that is, by the way.) Had they lived in a more placid era, he theorizes, the Beatles might never have reached the same heights of creativity.

But they did, and we all benefit from it, with the delights of Sergeant Pepper, the White Album and Abbey Road to come.

All in all this is a terrific book, full of anecdote and great quotes from interviews done then and since, and about something important: how creativity happens – and why.

#Beatles #AgeOfOlympus @TitanBooks

No Comments